Focus: Energy Transition at What Cost

Author: Nicolas Sioné

The materials underpinning such transition

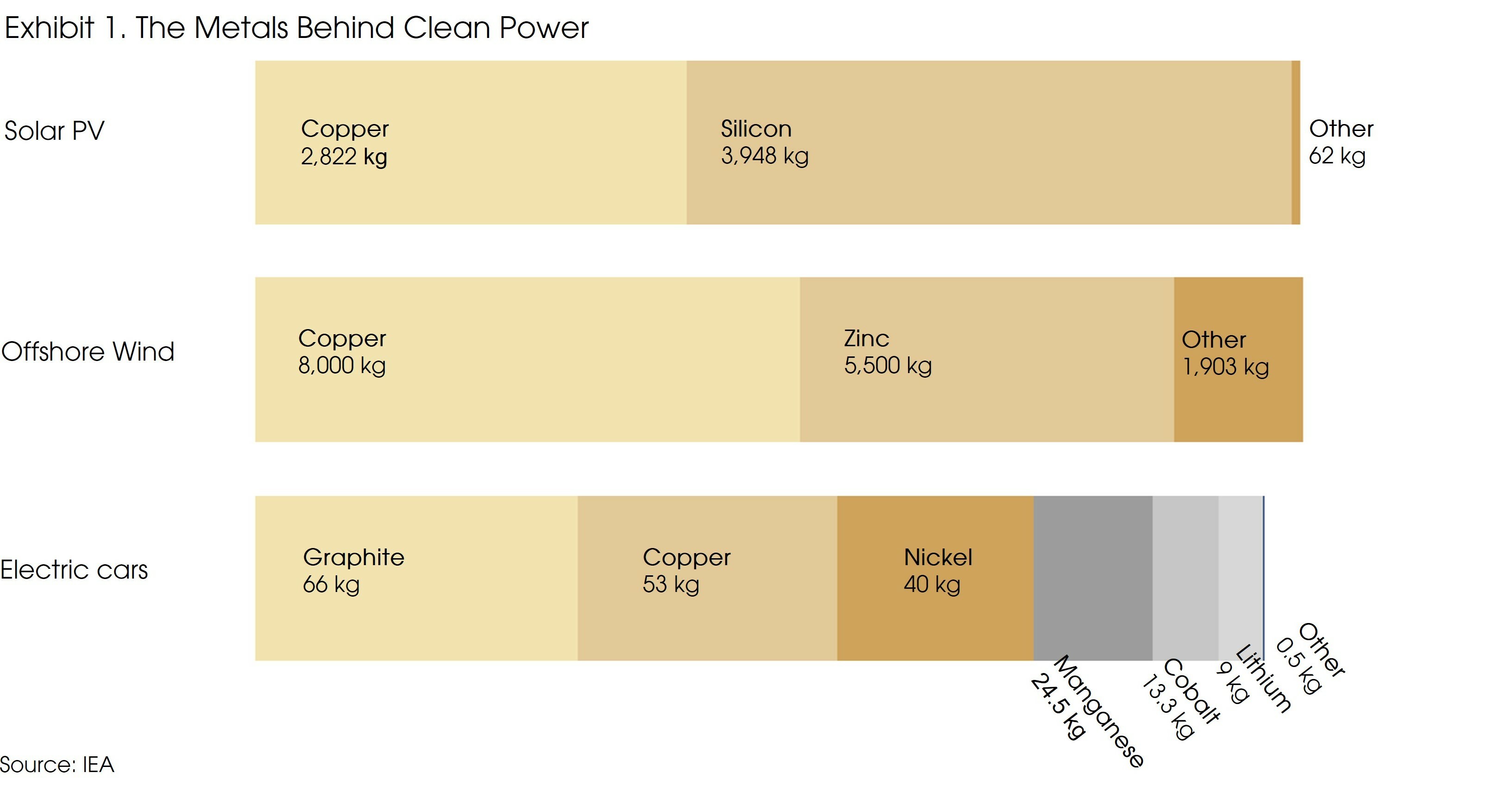

Achieving a net-zero-emissions economy by mid-century will require a profound reshuffling of the energy system, with a major shift from carbon-intensive fossil fuels to clean energy sources. As one can imagine, the rebasing of our energy mix and development of alternative clean energy sources will require significant investment and the supply of key raw materials such as metals and REEs (Rare Earth Elements), to the tune of 3 billion tons.

Over the past three years, environmental, macro-economic and geopolitical shocks have put the global energy transition under pressure. High energy prices, risks of energy supply shortages and shortfalls in meeting climate goals now threaten the three imperatives for a smooth energy transition, namely: energy affordability, security, access and sustainability.

If we are to meet climate goals in agreement with the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero by 2050 Roadmap the ramp up and investment requirements to be implemented in the metals industry are huge.

Let’s take as an example a typical electric battery pack. Such an item would require 8 Kg of Lithium, 35 Kg of Nickel, 20 Kg of Manganese and 14Kg of Cobalt, while charging stations require significant amounts of Copper.

Production and pricing

Metal prices have already seen large increases as economies re-opened ensuing to the Covid crisis, highlighting a critical need to analyze what could constrain production and delay supply responses. Another key aspect to assess will be the availability of such metals and minerals when facing the needs of low carbon technologies.

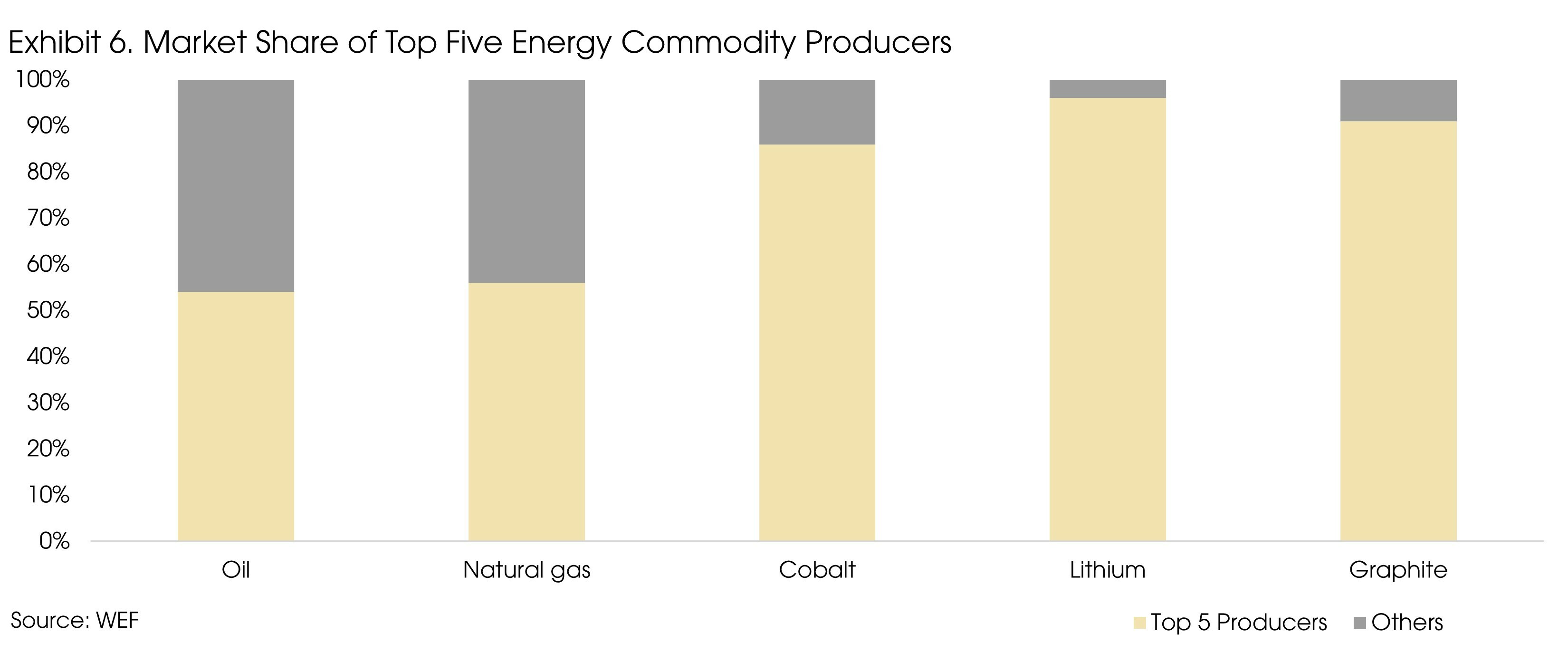

According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), “replacing fossil fuels with low carbon technologies would require an eightfold increase in renewable energy investments and cause a sizable increase in demand for metals and REEs. However, developing mines is a very lengthy process (often a decade or more)”.

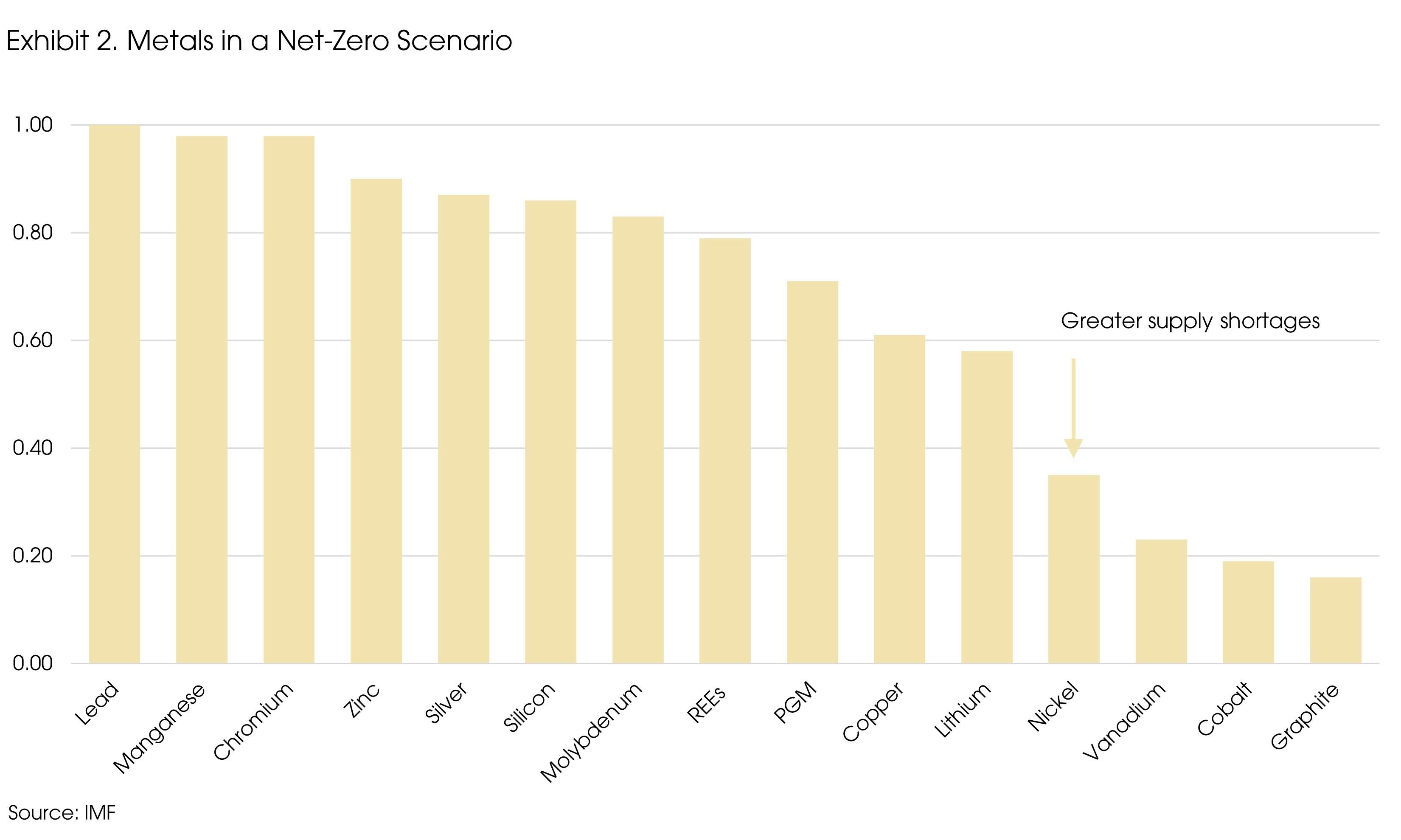

As outlined in the IMF chart below, given the projected increase in metals consumption that a net zero scenario would impose, current production rates of graphite, cobalt, vanadium, nickel, copper and lithium seem vastly inadequate.

The previous commodities production downturn has led to a significant capacity cut in the sector. Technology advancements in the metal mining sector has been limited, and capacity resumption tends to take some time (e.g., 2-3 years for cobalt miners). Also, as the mining sector is still relatively labor-intensive, labor disputes may emerge upon rebuilding capacity, promoting supply uncertainty. In addition to the above, the focus on capital discipline adopted by mining companies is expected to continue to constrain supply, thus indicating that the sector peak has yet to be reached.

The immediate question that then comes to mind is whether production can be scaled up. According to the WEF, and as production is not thought to be static, existing mineral deposits would allow for greater production through more investment in extraction and exploration, as is the case for graphite and vanadium. For other minerals, remaining deposits could be a constraint on future demand. One must note, the rising trend of metal recycling is also anticipated to contribute to increasing supply. However, at the moment the reuse of scrap metals only occurs on a large scale for copper and nickel, while we are beginning to see traction for scarcer materials like lithium and cobalt.

Complicating factors

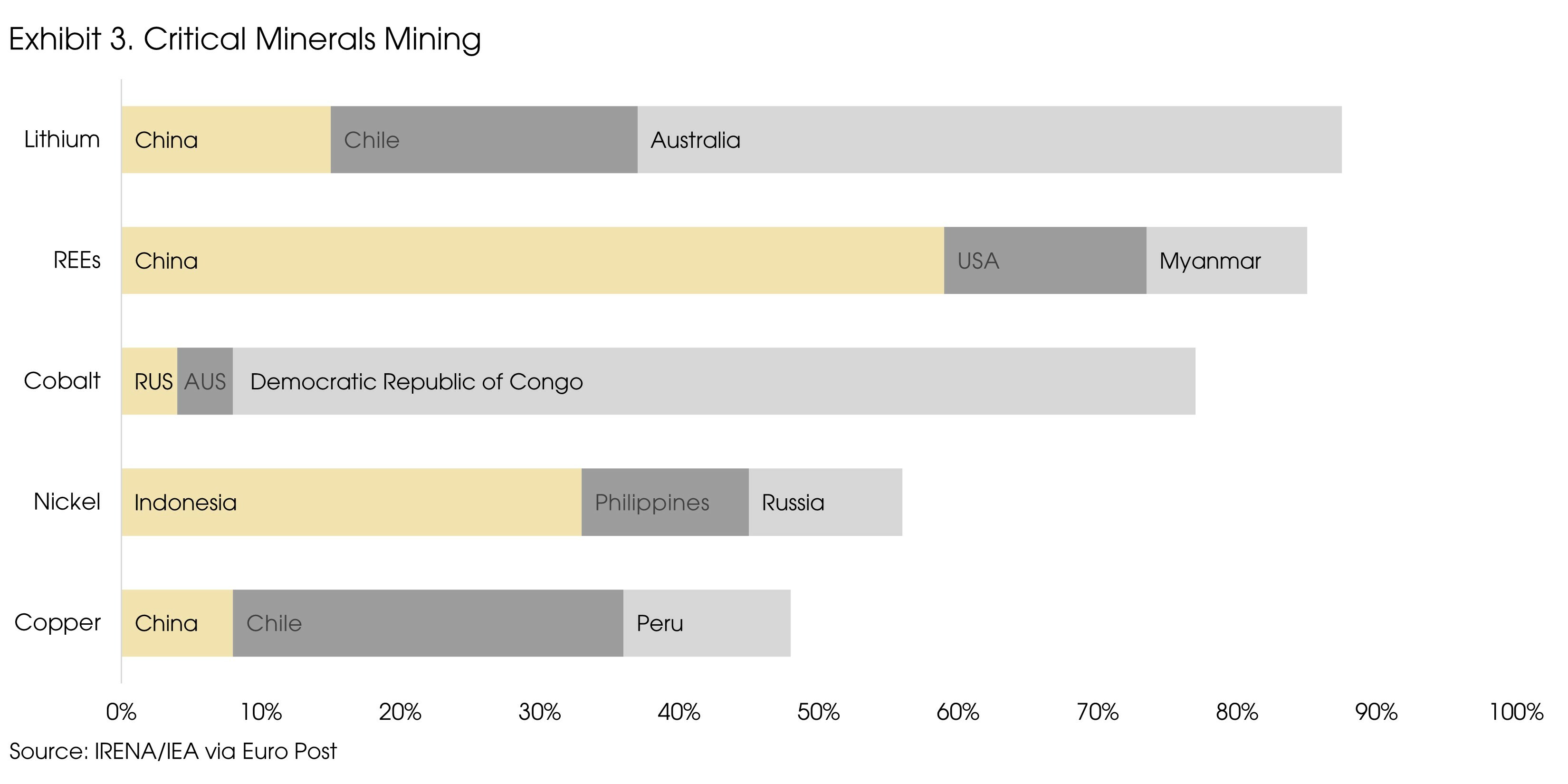

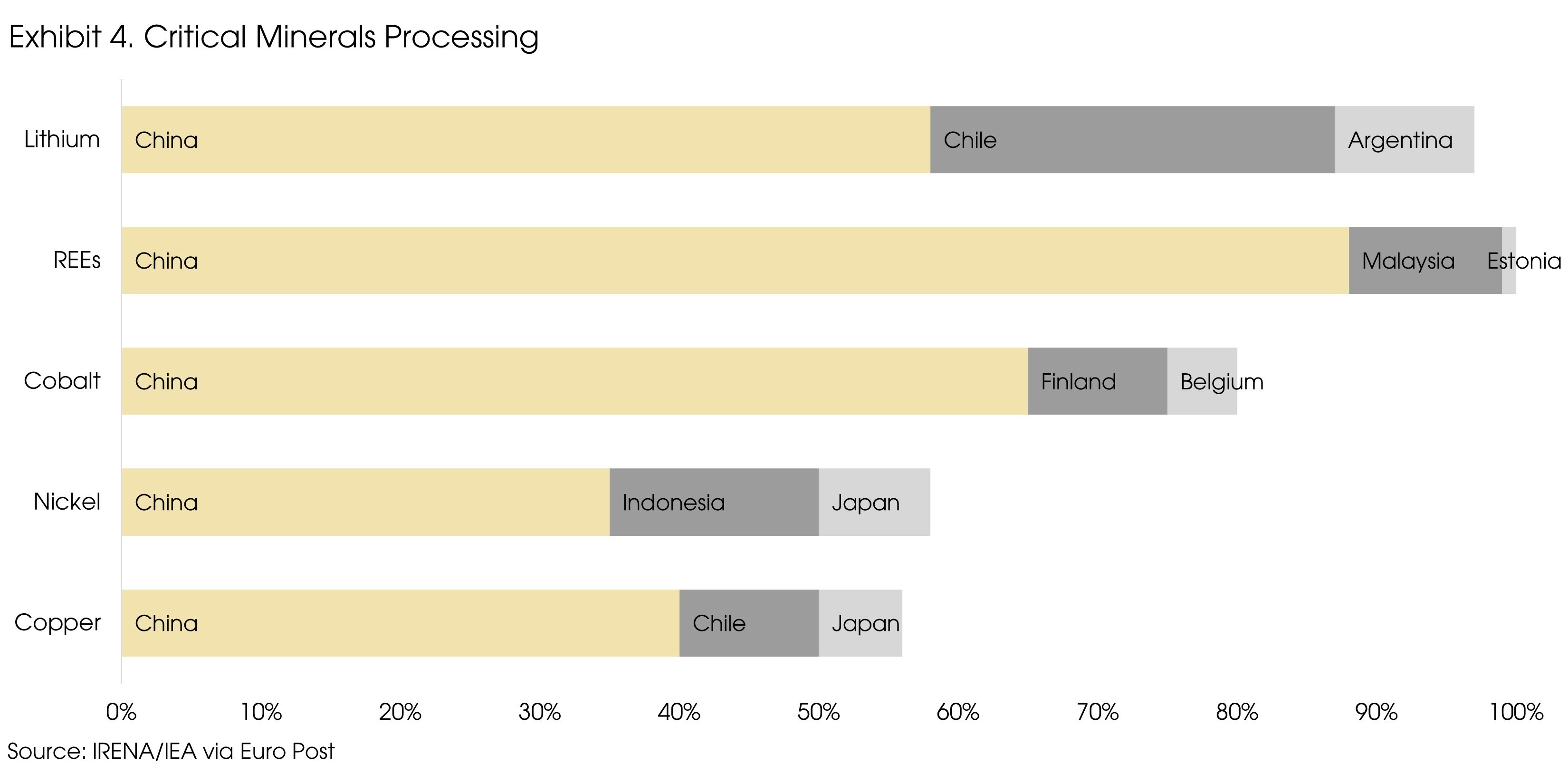

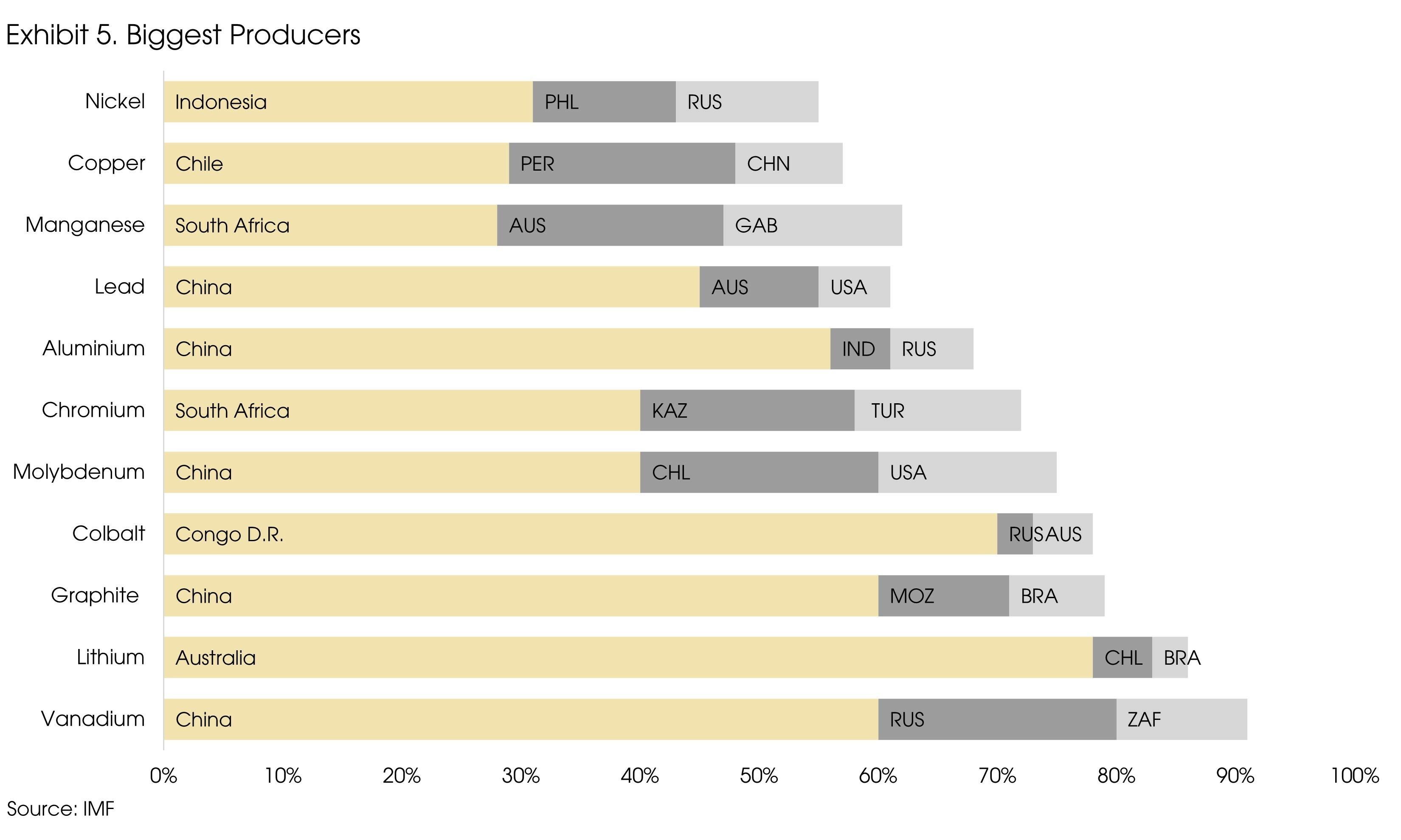

Supply in critical metals is generally very concentrated, implying that only the few producers will benefit from growing demand. Conversely, this outlines a clear energy transition risk should investments in production capacity not meet demand, or in case of potential geopolitical risk inside or between producer nations.

Ensuing to a long stream of investments across the globe, China currently stands as the lead global supplier of a wide range of key materials including titanium but also as a leader in terms of specialized processes to mine and refine Rare Earths Elements and other strategic metals. China refines 80% of world’s cobalt, 68% of global nickel and graphite and 60% of the world’s lithium. A dominant role that could impact energy transition should mining operations remain stagnant. Disruptions in producing countries’ institutions, regulations or policies could add further complexity in supply growth.

Prices could reach historical peaks for unprecedented lengths of time – and even delay the energy transition itself.

Financing concerns

When looking at investors’ investment criteria, ESG constitutes somewhat of a challenge considering the mining sector, as current extraction techniques imply environmental impacts that go against environmental preservation and global warming policies. Reduced access to capital for companies with lower ESG ratings could contribute to constrain production. In response, miners are trying to reduce their carbon footprint.

According to the WEF, an S&P Global analysis shows that the ESG average score of the S&P Global 1200 (an index representing about 70% of global stock-market capitalization), stood at 62%, while the metals and mining sector’s score rose to 52% last year from 39 in 2018. Miners are catching up with other sectors to become more attractive from a social responsibility perspective.

Policy implications

Achieving a transformation of the energy transition’s magnitude and complexity requires long term policies, enabling infrastructures, and significant investment. Such a shift will also demand changes in consumers behavior and consumption habits to improve demand efficiency.

In light of the pace at which our energy transition needs to be enacted, the world has no choice but to react in a credible, globally coordinated fashion when implementing climate policies. Such a collegial approach would contribute to direct investment towards the expansion of the metals and REEs supply, aiding our clean energy transition. Reduced trade barriers and export restrictions would allow markets to operate efficiently.

As mentioned prior, investments within the segment are and will be conditioned by policy decisions and their speed of execution. It is unfortunate that still at this stage of urgency, policies are not brought to the market in a globally coordinated fashion. The lack of coordination combined with exogenous geopolitical or macroeconomic factors are detrimental to the energy transition process, as they may hinder mining investments and raise the odds that high metal prices derail the sought after and needed energy transition.

Regulations and policies that accompany energy transition and climate change as a whole need to be robust and stringent enough to drive necessary action and investment. One could believe that for climate commitments to be respected by the various stakeholders, commitments should be legally binding and include enforcement mechanisms to ensure swift implementation and sustainability of such ventures.

Similarly, mobilizing necessary investments from public and private sources requires policy and institutional stability, appropriate de-risking mechanisms, and effective international collaboration to support the investment needs of developing countries.

Are we set to walk the talk?

The world needs more low carbon energy technologies to keep temperatures from rising any further, and the transition could unleash an unprecedented demand for metals. While deposits are broadly sufficient, the needed ramp-up in mining investment and operations could be challenging for certain metals and may be derailed by market or country specific risks.

On the flip side, prices may decrease more than expected if legislative approval and government actions required for the energy transition and infrastructure programs do not materialize as expected.

The need to urgently accelerate the energy transition is clear. The current market scenario, as volatile as it is, presents a unique opportunity to do just that by speeding up energy transition projects and building up resilience in the energy systems. Winning the race requires stakeholders at every level and in every geography to step up and work together on reducing demand for fossil fuels, ramping up clean energy consumption in a way that lays the foundation for a sustainable future that is both inclusive and sustainable. The energy transition, along with increased use of high-end technological products and processes is encouraging capital expenditure by not only China but other countries as well.

Our progression along the sustainability path has nevertheless made us aware that we cannot, a priori, rely exclusively on clean or renewable energies as they stand today. Within the context of this energy transition, nuclear will have to be reconsidered so as to bridge demand away from traditional fossil fuels while ramping up in investment, research and exploitation of renewables sources of clean energy.

Sources: IEA, IMF, IRENA, WEF, CIGP Estimates