CIO Viewpoint: China New Economic Chapters in the Story

A Refined China Consensus

Short term noise continues to bemuse the markets. One day it is central bank language, another it is a tweet and another it is about an oil tanker. Our view of an impending synchronized slowdown has been reaffirmed as even the IMF downgraded global growth forecast for the second time this year to 3.2% globally in 2019 and 3.5% in 2020 (prior downgrade was in April). Global central banks’ vernacular, the US-China trade negotiations and now the potential currency war have influenced investors more than second quarter earnings and simple fundamentals. These segments of turmoil have dinged risky assets but they have promptly been followed by market calm. This is what concerns us most and this is what is likely contributing to volatility – the up and the down – not just the down. This is why we have been largely risk off this summer after taking gains in April [See our May Viewpoint.] We think the market desperately wants to ‘go-green’ and it therefore ignores the deterioration of business economic data: from the US to Germany to China. Businesses are often a leading indicator of consumer reactions. After all, consumers drive much of developed market GDP globally. For investors, the USD 16tn in global negative yielding debt is not helping asset allocators. A global wall of worry reminds investors of the perils of the economy at this juncture; China included.

Vacation

Chinese party officials from all levels have been on a staggered “holiday” in the summer resort town of Beidaihe, approximately a three-hour drive from Beijing. While news from the annual event is incredibly sparse: no leaks, no agenda, no timeline, no pressers. It is generally understood that committees of all the parts of the party gather at various times to not only formulate a ‘X’th five-year plan for the country but share thoughts on pending urgent global issues: political and economic.

Ever-ongoing is the trade dialogue with the United States. While we thought more progress would have been made at the G20 meeting in Osaka on June 28, in fact it was simply a call to meet again, which US Trade Representative Lighthizer and his team did in Beijing in July. That culminated in an agreement to meet again in September. Unfortunately, we think progress has been minimal at best since the infamous May tweet from President Trump and we do not expect much result in September. Markets are likely to be disappointed as we do not think they have priced this in yet. While the US claims to have collected USD 63bn of tariffs through June, it is believed the Chinese negotiators are under an edict to elongate discussions at this juncture in the hopes that it can be leveraged to influence the 2020 US presidential elections. China has other tools to dampen the immediate impact of tariffs, though President Trump also says he “can do a lot more”. We still expect trade rhetoric to cycle in and out of market headlines for the foreseeable future.

Less Lending for Stable Growth

In July 2018 Chinese leaders initiated a strategy to focus more on “growth stabilization” over and above debt reduction. In January 2019 the Chinese central bank cut the reserve requirement by 100 bps to try to stimulate credit growth, which is typically a prime booster of economic activity. This is at odds with China’s multi-year decree to reform and reign in lending. This explains the disconnect some Western investors may have of how China is sustaining its outstanding credit deficit (total debt greater than 300% of GDP as of June 2019) and the typical headlines about traditional monetary tool implementation by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC). Further to growth stabilization, during the National People's Congress meeting in March 2019, authorities announced the first stimulus package of the year that included, among many initiatives, selective and temporary reductions in VAT to try to promote spending by both consumers and businesses. China has been encouraging consumer spending for several years in order to transform the economy away from reliance on government spending as a booster of economic growth.

Bad Banks

In the middle of all these economic policies, it is notable that two rural Chinese banks were recently taken over by investors and the government, in order to save them from default. In July, the government directed ICBC, China Cinda Asset Management and China Great Wall Asset Management to invest USD 436mn in Bank of Jinzhou, a rural community bank. This follows the bank’s shares being suspended in April after its auditor resigned. In June, Baoshang Bank, an Inner Mongolia-based commercial lender, was similarly “taken-over” by the PBOC and the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission after its shares, too, had not traded for a year. In both cases the banks’ debt piled up to become unmanageable. While China has shifted its focus to growth stabilization, in reality credit issues remain.

Magnificent Manipulation

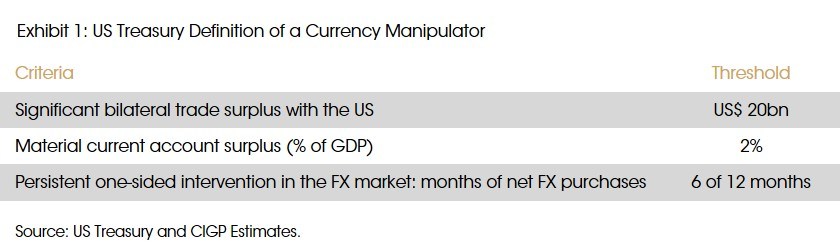

The recent weakness in the RMB against the USD, crossing 7 RMB per 1 USD, has been noted widely in the press. Such moves can impact markets and policies in various ways. Some are: (1) greater interest expense of Chinese issuers of offshore bonds, (2) cheaper exports, which is a key facet of the Trump administration’s argument: “unfair”, (3) imports are more expensive to China, (4) greater pressure on capital conversion from China to outside China. The US administration likely believes that this is a tactic employed by China to weaken the impact of tariffs imposed on it. In October 2018 the US Treasury was already considering labeling China a currency manipulator. It had also listed Switzerland, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and Germany as under consideration or actively manipulating. There are many ways in which a country can manipulate its currency and countries may go on and off the US list. [See Exhibit 1.] There is an element of subjectivity to actually announcing the status and there are reasons to think that this is part of a strategy adopted by the Trump Administration. Furthermore, the U.S. Treasury’s ability to enforce consequences is limited. When it comes to trade, pressure from the WTO towards China has had limited impact which might be why the US is now trying to leverage the IMF. However, the label of currency manipulator imposed by the US Treasury, is only the first step to a potential complaint to the IMF. Even if the IMF also has limited powers to enforce consequences. Thus, this is just another headline confusing markets and contributes to the increase of uncertainty.

Offshore Debt Impact

What’s important to note for debt holdings is that it will become more expensive to service if more RMB is required than in the past to pay that interest expense. However, Chinese policy makers have implemented various credit polices over the years to control outsized debt issuance that could have been exacerbated by currency depreciation. Most notably, China has moved to reduce new issuance of offshore debt and shift that demand to encourage refinancing of such offshore debt. Accordingly, the overall total does not grow as exponentially as it might have to satisfy the demand for credit by Chinese SOEs, real estate companies and private enterprises. Furthermore, all debt offerings are passed through the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) and the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). This has tightened availability of financing, and increased investor demand for Chinese bonds. Ideally these reforms should result in more prudent financial decisions by Local Government Financial Vehicles (LGFV) and real estate companies. Both are the largest issuers of offshore debt.

In the first five months of 2019, Chinese companies sold ~ USD 99.2 bn worth of offshore bonds, on top of ~ USD 235.8 bn last year, mostly in USD, HKD, and RMB, according to the NDRC. Real estate companies have sold approximately USD 32bn worth of offshore notes this year, while LGFVs issued USD 5.4bn in notes, according to Bloomberg data. For the market, this means extra prudence, patience, and active management in order to try to successfully navigate the minefield.

Sticky Stimulus

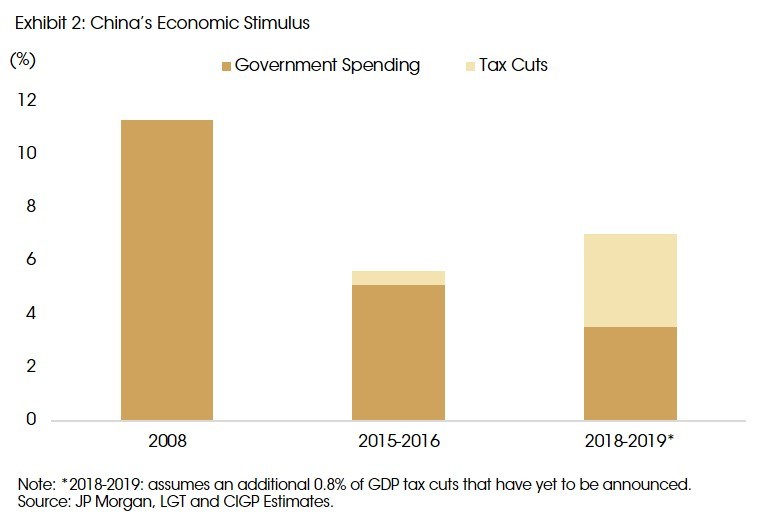

All told, we expect another stimulus package to be announced this year. Chinese authorities will likely wait until a dire moment in order to stem the effect of a trade war and resulting tariffs. We do not think the wait will be too long as the party will want to show a good image for the October 1 National Day celebrations. [See Exhibit 2.] After all, food prices rose more than 9% in July year on year. This is in part largely due to the surge in pork prices due to swine fever (prices rose 33% year on year but have not reached the June 2016 peak). While such stimulus is not a direct result of the Beidaihe meetings but rather just the remit of the PBOC (People’s Bank of China) to achieve “stable growth”, it shows how fragile China is economically. The party is fearful of unrest whether due to inflation, food accessibility, scandals, corruption, and fraud, among other issues. An underlying goal of the party is stability. [See our March Viewpoint.] Thus the mantra of growth stabilization is used to assuage Chinese consumers.

Stimulus measures are often a way to ensure greater probability of successful investment and positive return. When a government commits to spending on infrastructure, transportation, subsidy programs, or shifts policy to attract investors, outsized economic profit can usually be garnered. We continue to follow economic policy development from the PBOC and NRDC and other bodies for clues as to how China will manage this sticky situation of stability and growth.

What to Do

Because of the continued pivot to negative yields and lower (yield) for longer [see our July Viewpoint.], market participants have been seeking riskier assets to try to achieve expected return targets over a given investment horizon. Therefore we continue to suggest a return to fundamentals and to move up in quality when it comes to fixed income, globally but especially in Asia. We still think there are some remaining returns in equities as corporate fundamentals generally remain strong though it depends on the sector.

While we advocate a long term stable allocation to emerging markets, and especially Asia, where opportunities can still be found, it will likely become a crowded and bumpy trade in a lower for longer environment. Asia alone may not make up the difference and a serious consideration of alternatives which hold a greater predictability of return due to its' counter cyclical nature, may come under more serious consideration by the market and investors.

Sources: Bloomberg, CNBC, International Monetary Fund (IMF), Investcorp, JP Morgan, LGT Private Bank, Lombard Odier, People's Bank of China (PBoC), Pictet, Reuters, US Treasury, Wall Street Journal and CIGP Estimates.